Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who wrote the famous 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, has died at age 87.

I haven't found any obituaries yet, but here's the announcement on his Facebook page.

In 2010, when I made a list of "the 12 books that have influenced me the most," I included Flow.

This post by Ann Althouse (my mom) quoted the book's summary of 8 features of the state of "flow":

First, the experience usually occurs when we confront tasks we have a chance of completing. Second, we must be able to concentrate on what we are doing. Third and fourth, the concentration is usually possible because the task undertaken has clear goals and immediate feedback. Fifth, one acts with a deep but effortless involvement that removes from awareness the worries and frustrations of everyday life. Sixth, enjoyable experiences allow people to exercise a sense of control over their actions. Seventh, concern for the self disappears, yet paradoxically the sense of self emerges stronger after the flow experience is over. Finally, the sense of the duration of time is altered; hours pass by in minutes, and minutes can stretch out to seem like hours. The combination of all these elements causes a sense of deep enjoyment that is so rewarding people feel that expending a great deal of energy is worthwhile simply to be able to feel it.

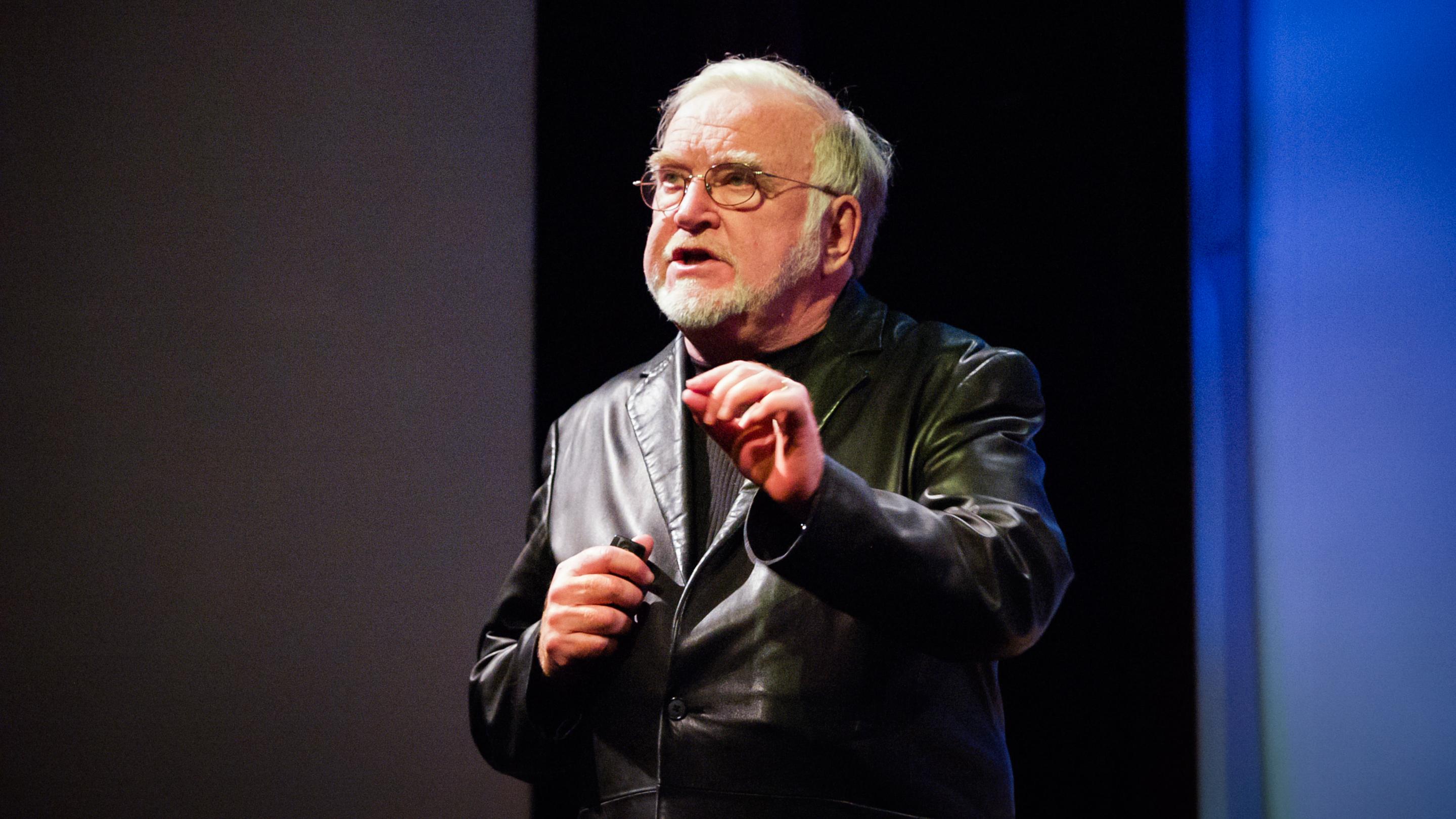

Here's Csikszentmihalyi's TED talk from 2004: "Flow, the secret to happiness."

In Psychology Today, English professor Vivian Wagner wrote in 2018:The flow state, a concept first recognized and analyzed by positive psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi …, is a worthy goal for anyone who wants to think and live more creatively. … In my composition classrooms, I often have students "freewrite" about whatever topic we’re focusing on that day. I find that while they’re freewriting, they enter a state of flow. … This is an especially valuable state because it’s then that creative connections are made. The mind allows itself to think, without the constraints and expectations of the external world. There’s time enough later to look at what we’ve written while in a flow state, but it’s important to be able to stay there for as long as possible in order to reap the benefits from it. … In our era of multiple distractions, it can be difficult to slip into a flow state. Often, in the middle of doing something — when I might actually be in a flow state — I stop to check my phone or my email or search the web, and those activities break it up. More even than when Csikszentmihalyi first theorized about flow, we’re in great need of it today. … It’s a beautiful, mysterious process — one that will change your life for the better and bring in a daily dose of creativity. And during those moments of flow, you’ll find yourself making connections, forming ideas, and thinking differently.

(Photo of Csíkszentmihályi from his TED talk.)